|

Hornsby Shire Council

|

Attachment to Report No. EN38/08 Page 0

|

The Catchments Remediation

Rate Capital Works Program

Annual Performance Report

2007/2008

Prepared by the Water

Catchments Team

September 2008

Cherrybrook Lakes, Cherrybrook (Water Quality

sampling site)

The 2007/2008 Catchments Remediation Rate Capital

Works Annual Performance Report was prepared by Elizabeth Bulley and David Beharrell of the Water Catchments Team,

Environment Division, Hornsby Shire Council. The report was prepared under the

supervision of Ross McPherson, Manager, Water Catchments, and under the

direction of Robert Stephens, Executive Manager, Environment Division.

For further information contact:

Water Catchments Team

Hornsby Shire Council

PO Box 37

Hornsby

NSW 1630

Phone: (02) 9847

6860

Fax: (02) 9847

6598

Email: dbeharrell@hornsby.nsw.gov.au

This report aims to provide quantitative data and

analysis of the relative performance of different water quality treatment

measures, including gross pollutant devices, sediment basins, wetlands and

bioremediation systems that have been constructed to improve stormwater quality

in Hornsby Shire. The results of the report will be used by stormwater and

catchment managers to provide a better insight into determining the type of

structures that are suitable for specific sites. Furthermore, the data provides

valuable information about the costs (both capital and maintenance), benefits

and device optimisation which can aid in the formulation of strategies to

improve catchment/landuse practices by both structural and non-structural

means.

The principal objective of installing stormwater

treatment measures is to improve the quality of stormwater by removing

pollutants and in some instances retaining stormwater flows. In 2007/08, 16

catchments remediation capital works projects were completed at a total cost of

$957,000. These works involved the construction and/or installation of 11

sediment basins, four end-of-pipe gross pollutant traps, eight stream

remediation projects, one bioremediation basin and six stormwater gardens.

While these structural interventions provide

treatment of pollutants, the Catchments Remediation Program also promotes and

funds non-structural initiatives in the pursuit of improving stormwater quality.

These include: monitoring, maintenance, ensuring stormwater controls on new

development sites, street sweeping, environmental education, business auditing,

compliance programs and pollution clean-ups.

The

collection of performance data over the 2007/2008 financial year has allowed

Council to examine the indicative maintenance costs and gross pollutant

(sediment, litter and organic matter) removal from Council’s 370 + water

quality improvement devices. The results show that 1236 cubic metres of sediment, litter and organic matter was removed

from the Shire’s drainage system and waterways over an average 13 separate

cleaning events.

The total

cost to Council to maintain its water quality assets and adjacent landscaped

areas was $354,000. This cost included device inspections, cleaning and

desilting, material processing for reuse, disposal of litter to landfill, asset

maintenance and repair, landscape maintenance and weed control in and around

assets and maintenance of leachate treatment and reuse facilities. The annual maintenance cost was more than

previous years which can be attributed to two large maintenance projects: 1)

the remediation of the Mt Colah stockpiling site ($87,000), and 2) Dredging the

Lakes of Cherrybrook ($45,000), and the increased cost incurred by having to send

recovered material to landfill.

The report

also provides information on costs, sizing and performance of wetland ponds

constructed under the Catchments Remediation Program. In addition, Council has

embarked on a program to remediate degraded creeks and former landfill sites

and trial new and innovative stormwater infiltration, reuse and bioremediation

systems. Of particular interest in the

2007/2008 period were the bioremediation basin and stormwater gardens

constructed at Cheltenham and Berowra.

Overall, the findings of this report give stormwater

managers a better insight into the cost-effectiveness and performance of water

quality improvement structures and the management of life-cycle costs for

individual stormwater quality assets. The performance of these devices allows

Council to both refine and modify the design of future water quality control

measures, and judge their appropriateness for proposed remediation sites based

on catchment size and land use impact.

|

Hornsby Shire Council

|

Attachment to Report No. EN38/08 Page 3

|

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE

SUMMARY. 3

1.0 INTRODUCTION. 5

1.1 Report Objective. 5

1.2 Background. 5

1.2.1

Catchments Remediation Program.. 5

1.2.2

Catchments Remediation Rate (CRR) and Panel 6

1.3

Statutory Considerations. 7

2.0 Selection

and implementation of the CRR Capital Works. 9

2.1 Selecting

a stormwater treatment measure. 9

2.2 Project

Management and Construction. 9

2.3

Maintenance Considerations. 9

2.4 Maintenance

Operations. 10

2.5 Occupational

Health and Safety (OH&S) and Risk Management. 11

3.0 Stormwater Treatment

Measures. 12

3.1 Gross

Pollutant Devices (GPD’s) 12

3.1.1. Trash Racks (21) 12

3.1.2. Litter Baskets (10) 14

3.2 Gross

Pollutant Devices - Proprietary (247) 14

3.2.1. Net Techs/Pratten

Nets/Channel Nets (44) 14

3.2.2. Underground Vaults

(20) 15

3.2.3. Ski-Jump Litter Traps

(4) 15

3.2.4. Pit Inserts (170) 15

3.3 Constructed

Wetlands. 16

3.4 Sediment

Basins. 17

3.5 Stream

Remediation. 17

3.6 Bioremediation

Basin - Castle Howard Road, Cheltenham.. 20

3.7 Stormwater

Gardens - Turner Road, Berowra. 21

3.8 Developer

Constructed Devices. 22

4.0

PERFORMANCE EVALUATION AND COSTS. 23

4.1 Rainfall measurement. 23

4.2 Performance

of Gross Pollutant Devices. 23

4.2.1 Pollutant Removal Trends. 23

4.2.2 Maintenance Costs. 26

4.2.3 Dredging Lakes of

Cherrybrook. 26

4.3 Wetland

Performance. 27

4.3.1

Pollutant Removal Trends and Costs. 27

4.4 Material

Disposal and Reuse. 28

5.0 LANDSCAPE

MAINTENANCE AND BUSH REGENERATION. 30

5.1 General

Maintenance Considerations. 30

5.2 Maintenance

of Landscapes surrounding Gross Pollutant Devices. 30

5.3 Maintenance

of Wetlands. 30

6.0 LANDFILL

REMEDIATION. 32

6.1 Foxglove

Oval, Mount Colah. 32

6.2 Arcadia

Park, Arcadia. 33

7.0 STREET SWEEPING.. 34

8.0 CONCLUSIONS. 35

9.0 REFERENCES. 36

Appendix

A: Rainfall data for Hornsby LGA. 37

Hornsby is located 25 kilometres north-west of the

Sydney CBD and is the Council base for a Shire covering approximately 50,990

hectares and serving the needs of more than 157,000 residents. The Shire

extends from Epping in the south to Brooklyn and Wisemans Ferry in the north

fronting a large expanse of the Lower

Hawkesbury River.

A majority of the northern and central Shire consists of Regional and National

Park and Nature Reserve. This unique natural character combined with the many

creeks and estuaries has led to Council being termed the ‘Bushland Shire’.

In an attempt to conserve the ecological value of the

Shire’s many natural waterways and to improve the quality of urban stormwater

Hornsby Shire Council has taken an integrated approach to stormwater quality

management by developing a range of capital and non-capital (preventative)

measures. This initiative includes all major catchments under the Stormwater

Management Plan framework, together with more closely modelled sub-catchment

plans. Council’s progressive strategy has recognised the need to tackle these

challenges using a broad approach to understanding and managing the total water

cycle. This has led to the development

of a Sustainable Total Water Cycle Management Strategy (2005).

This report focuses on the performance of different

stormwater quality control structures e.g. gross pollutant devices, constructed

wetlands, sediment basins, stream remediation and leachate treatment works that

have been constructed under Council’s Catchments Remediation Rate (CRR) Capital

Works Program.

To provide quantitative data and an analysis of the

relative performance of different stormwater and leachate quality improvement

devices that have been implemented under the CRR program. Specific reference

will be made to those devices constructed and/or installed in the 2007/2008

financial year.

In response to

general water quality degradation, including red algal blooms and fish kills in

the Berowra Creek estuary in September 1993, Hornsby Council placed a

moratorium on all development assessments within the catchments of the West

Hornsby STP. To resolve this, the

Minister for Planning established a Technical Working Party (TWP), comprising

representatives of Council, the Water

Board (Sydney Water) and the Department of Urban Affairs and Planning

(DUAP). Representatives from the

Environment Protection Authority (EPA) and the Hawkesbury-Nepean Catchment

Management Trust joined the TWP in early 1994.

The TWP confirmed that the two Sewage Treatment Plants (STP’s) contributed

to the poor water quality of the creek.

Moreover, it highlighted the significant role of polluted urban

stormwater, particularly runoff from developing and newly developed residential

areas.

On 27 April 1994, the

participating organisations of the TWP signed a Statement of Joint Intent (SoJI

- also known as the Community Contract for Berowra Creek) agreeing to work

together to achieve the ecologically sustainable development (ESD) of the

Berowra Creek catchment and the recovery of the environmental health of the

creek. The Community Contract, included

agreements to upgrade the STP’s and it bound the parties to the preparation and

implementation of a Water Quality Management Strategy. It also required Council to prepare and

implement a strategy to reduce stormwater nutrient ingress to Berowra Creek and

to utilise water sensitive design in its consideration of future developments.

However, the level of pollutants and the urgent need

for action was not confined to Berowra Creek. Water quality in the other major

catchments within the Shire had also deteriorated because of urbanisation.

Remedial works to reduce pollution and improve water quality were required

throughout the entire Shire including relevant areas draining the Cowan Creek, Lane Cove River and the Hawkesbury River

catchments.

In 1995, the Water Catchments Team initiated the first

phase of the ongoing strategic planning for catchment management within the

Shire. The result was the production of a Catchments Remediation Program

Five-Year Plan which detailed the proposed expenditure of the Catchments

Remediation Rate towards meeting the objectives of the Statement of Joint

Intent and in turn improving water quality in the Shire’s waterways. The Plan

included financial forecasts of rate income over a five year period together

with capital investment and non-capital expenditure including asset management.

It was hoped that Hornsby Shire Council’s Catchments

Remediation Program would give stormwater managers a better insight into the

cost-efficiency and performance of individual devices, but more importantly,

monitoring of devices will reflect the individual characteristics of

sub-catchments and the associated point sources of pollution, which can be

targeted through pollutant minimisation strategies. It was also seen that

community and industry awareness projects are important to complement the

Catchments Remediation Program, whilst Local Government can also review work practices

and strategies in relation to sediment and erosion controls on building sites

(and there enforcement), street sweeping, street tree planting, rubbish

collections and kerbside recycling collections.

Additional objectives of the

Catchments Remediation Program, which still apply today, aim to address:

· Innovation – products and services – generate and use

ideas to add value to the community as stakeholders, provide productivity

improvements, continue leadership and management capabilities in local government

· Health and safety – provide a safe and healthy aquatic

environment for the community, council staff and contractors

· Performance – better understand community needs and

expectations, ensure/deliver reliability, durability, quality and maximise the cost/benefit

of installed capital projects

· Justify expenditure

through regular reports to the community, protect and service assets and

continually improve operations.

Council’s catchments remediation work up to 1997 was

only partly funded by the CRR, with the majority of funding being at the

expense of other traditional Council services e.g. Parks. However, the cost of

Council’s ‘Statement of Joint Intent (SoJI) for Berowra Creek’ obligations and

remediation works in the other catchments was highlighted to be much more than

was covered by the rate. The proposal to increase the CRR from 2% to a 5% levy

on ordinary rates in 1997 was presented with the idea to accelerate remediation

capital works and return resources to traditional services that had suffered

funding cuts. The increased funding was intended for planning, design,

construction, maintenance and management of remediation devices. The proposal

to increase the CRR to 5% was adopted by Council on the 13th April 1997

and still applies today.

Approximately 50% of the CRR is directed to

non-capital costs including project management and a series of studies,

associated with meeting the SoJI objectives. These studies are designed to

identify more precisely the cause and effect mechanisms of pollution generation

in the Shire, develop effective longer term remedies for the problems, and

establish appropriate technological and monitoring techniques to determine and

report progress. The remaining 50% of

CRR funding is allocated to on-ground capital remediation works and subsequent

routine maintenance of all constructed devices. Current remedial environmental

protection works include the design and construction of wetlands, gross

pollutant devices or stormwater quality interception devices, leachate control

from old landfill sites, sediment basins and creek

stabilisation/rehabilitation.

The Catchments Remediation Rate

Expenditure Review Panel (the Panel) was established in July 1997 following

community consultation on increasing the CRR from 2% to 5%. The Panel meets

twice annually to review expenditure following the second and fourth quarters

of each financial year and currently comprises six community members, relevant

council staff and two nominated Councillor/s. The purpose of the Panel is to

ensure accountability and transparency of expenditure of CRR funds.

It should be noted that the

Hornsby Shire Local Environment Plan (LEP), 1994, permits Council to undertake

the construction or maintenance of stormwater drainage and water quality

treatment devices, bush regeneration and landscaping without obtaining

development consent. The proposals for construction are assessed under Part V

of the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act, 1979, which requires

Council to prepare a Review of Environmental Factors (REF). This identifies and evaluates the impacts of

an activity to determine whether the impacts are likely to significantly affect

the environment. The REF must also consider impacts of the activity on critical

habitat or threatened species, populations or ecological communities or their

habitat, under section 5A of the EP&A

Act.

The Threatened Species Conservation Act (TSC Act) 1995 specifies a set

of seven factors which must be considered by decision makers in assessing the

effect of a proposed activity on threatened species, populations or ecological

communities, or their habitats. These factors are collectively referred to as

the seven part test of significance.

The outcome of any

threatened species assessment should be that activities are undertaken in an

environmentally sensitive manner, and that appropriate measures are undertaken

to minimise adverse effects on threatened species, populations or ecological

communities, or their habitats. If the application of the seven part test finds

that a significant effect is likely then:

· A

Species Impact Statement must be prepared and the concurrence of the Director

General of the Department of Environment and Climate Change (DECC).

· The

activity may be modified such that a significant effect on threatened species,

populations or ecological communities, or their habitats is unlikely be sought.

Council is also required to notify and exhibit work proposals as per

Notification Protocol contained in Council’s Exempt and Complying Development

DCP (1999). This entire procedure has been quality assured under the NATA

certified ISO 9002 – Quality Management System and the ISO 14001 –

Environmental Management System, which the Water Catchments Team of Council

received in July 2000. These international standards will ensure that document

control, corrective and preventative actions and environmental procedures are

appropriately applied to all related projects.

1.4 Asset/

Lifecycle Management

Lifecycle

management enables Council to plan interventions, whether its maintenance or

renewal, at the optimum stage of an asset’s deterioration to enable cost

effective extensions of its useful life. There are a number of activities considered

in lifecycle management:

· Operations are those activities that have no effect on

asset condition but are necessary to keep the asset appropriately

utilised.

· Maintenance is the day to day work required to keep

assets operating at agreed service levels, and falls into two broad categories:

planned (proactive) maintenance is maintenance activities planned to prevent

asset deterioration; and unplanned (reactive) maintenance is maintenance

activities to correct asset malfunctions and failures on an as required basis

(e.g. emergency repairs). Maintenance

work is required to maintain the asset’s ability to provide the agreed service

level but does not extend the life of the asset. Operations and Maintenance expenditure are

considered an “Expense” for Council’s financial accounting purposes. A key

element of asset management planning is determining the most cost-effective mix

of planned maintenance in order to reduce unplanned maintenance to a minimum.

· Renewal work is the substantial replacement of the

asset, or a significant asset component, to its original size and

capacity. This work generally aims to

return the asset to a condition or state similar to the original asset.

· Replacements (or reconstruction) are those projects

that are created for the extension or upgrading of assets required to cater for

growth or to maintain or improve on the levels of service.

The

Stormwater Drainage Asset Management Plan (SDAMP) 2006 provides a financial

forecast for water quality assets in the Shire over a 20 year period. Cumulative

operating expenditure identified in the Plan, includes the cumulative

operation/maintenance expenditure and asset renewals and upgrades associated

with assets reaching their optimum life or age. To ensure

responsible financial management the assumptions made in the modelling were

very conservative. Hence, both renewal and projected maintenance cost were set

at a high level to allow for unforeseen circumstances or unpredictable rises in

costs.

The key feature of these financial projections is that

it is envisaged that in approximately ten years the opportunity for new capital

works across the Shire will steadily decline, resulting in a simultaneous

increase in operational and renewal costs. The life cycle analysis modelling of

catchment remediation program, as with Council’s Asset Management Plans, will

be reviewed at regular intervals to allow for the input of monitoring and

knowledge gained over time.

|

Hornsby Shire Council

|

Attachment to Report No. EN38/08 Page 8

|

2.0 Selection and implementation of the CRR Capital Works

The selection and implementation of structural

treatment measures involves six steps (Victoria Stormwater Committee, 1999).

These are:

1. Determine treatment objectives

2. Develop treatment train

3. Site identification

4. Short-list potential treatments

5. Compare potential treatments

6. Detailed design

Due to the varying degrees of expertise in different

fields the Environment and Works Division have forged a partnership approach to

deliver CRR capital works projects. Over the past 10 years, the Works Division’s

Design and Construction Branch has been able to incorporate the additional

design, construction and project management responsibilities associated with

CRR capital works into their annual civil works improvement program.

It is believed that there are a number of benefits

both to the Works and Environment Division and to the Council as a whole as a

result of this partnership. Some of

these are:

· Projects are developed ensuring compatibility with

local engineering and environment standards, and making sure that all issues

are addressed

· What is learnt from involvement in these projects is

utilised in all Council works so that we are setting the standards for

developers/builders to follow

· Opportunities for Works Division staff to be involved

in environmentally "cutting edge" technologies

· Involvement of staff in the Works Division in an area

of environmental management, with a flow-on effect resulting in better

understanding of sustainability issues

· Opportunities for Environment Division staff to become

more aware of engineering issues in the development of projects

· Potential expansion of the core business of the Works

Division.

The combination of the push towards competitive

tendering and the need to seek specialised engineering and contractor services

has also given management the impetus to consider contracting out or tendering

some of the design and construction activities. At present a small proportion

of the works is contracted out (usually low-risk remediation projects such as

stream remediation works and minor GPD’s) together with specialised design and

consulting services. As a result of this strategy, the Environment Division has

being satisfied at the quality of work achieved and the cost-benefit involved.

Included within the CRR capital works budget is

provision for monitoring and maintenance of all structures on a regular,

recorded basis. Due to the current strain on Council’s resources, the

increasing number of structures being built and the resulting demand for timely

and efficient maintenance, Council has continued to utilise contractors (on a 3

year contract) to undertake maintenance works under Council supervision.

Maintenance typically involves regular cleaning of

Gross Pollutant Devices (GPD’s) and periodic maintenance of sediment traps and

wetlands in terms of sediment removal, bank repair, weed control/spraying and

some general landscaping work. Fundamental design principles allow ease of

draining/flow bypass and access for maintenance of all water quality control

devices which results in efficient and cost-effective maintenance techniques in

the long term.

The existing contracts stipulate the contractor’s

responsibilities. These are outlined as follows:

· To maintain existing water quality remediation

structures to ensure optimal functioning and a weed-free surrounding landscape

· To ensure quality control/assurance throughout the

maintenance process incorporating:

o minimal

pollution of the site during cleaning and transport of materials

o efficient,

accurately documented records of contents removed and/or actions taken

o compliance

with Council’s environmental checklist

· The Contractor/s will be required to provide both a

status and cleanout report sheet for each structure after maintenance. Council

requires this to evaluate GPD performance, device accountability and

landscaping/bush regeneration costs per unit area

· The Contractor/s will be required to dispose of waste

material to a nominated landfill, or preferably a privately operated screening

recycling operation that offers a competitive rate per tonne (or compost onsite

in the case of vegetation). The only exception being the liquid/solid mix waste

removed by vacuum from wet sump devices such as the CDSâ, Humeceptor™ and Ecosol™ units. This waste shall be disposed of to an approved

location at Council’s expense

· That the Contractor/s has a proven record of

Occupational Health and Safety (OH&S) commitment, training and record

keeping.

The frequency of maintenance varies between treatment

measures. A majority of litter/gross pollutant devices need regular inspection

and maintenance after each significant rainfall event. In 2007/2008 Hornsby

Shire recorded approximately 50 large events (>10mm of rainfall in the

previous 48hrs) which resulted in higher than average yields (refer to Section

4.1).

Larger wet vault gross pollutant devices are inspected

and maintained on a quarterly basis, whilst constructed wetland and leachate

treatment systems are maintained on a more regular monthly schedule. Sediment

basins are inspected and maintained as required bi-annually. These basins need

periodic maintenance in terms of sediment removal, bank repair or minor

structural repairs. The scope of these works is based on additional quotations

for specific works, upon joint inspection by Council’s Superintendent and the

Contractor (see Table 2.0).

In 2004, Council engaged WBM Oceanics and Ecological

Engineering to prepare ‘Maintenance Guidelines for Stormwater Treatment

Measures’ under NSW Stormwater Trust funding. The resulting document provides a

detailed breakdown of maintenance procedures from planning and inspection

through to cleaning, disposal, monitoring and reporting.

Table 2.0 Maintenance Operations for

Stormwater Treatment Measures

|

Stormwater Treatment Measure

|

Inspection Frequency

|

Maintenance Frequency

|

Waste Destination

|

Reporting

|

|

GPD (end of pipe)

|

Storm event (>10mm in 48hrs)

|

Selective based on inspection

(within 5 working days)

|

Council material handling site.

Stockpiled for screening and reuse

|

Within 2 working days from

completion

|

|

GPD

(wet vault)

|

Quarterly (minimum)

|

Selective based on inspection

(within 5 working days)

|

Solids to Council material

handling site. Stockpiled for screening and reuse. Liquid fraction decanted

to passive open space.

|

Within 2 working days from

completion

|

|

GPD

(pit insert)

|

Monthly

|

Selective based on inspection

(within 5 working days)

|

Council material handling site.

Stockpiled for screening and reuse

|

Within 2 working days from

completion

|

|

Constructed wetland system or

Leachate treatment system

|

Monthly

|

Scheduled monthly

|

Weed material composted onsite.

Sediment tested for contaminants prior to disposal to landfill or reuse

|

Monthly

|

|

Sediment basin and Creek

remediation

|

Bi-annually or storm event

(depending on magnitude)

|

Selective based on inspection

(within 10 working days)

|

Weed material composted onsite.

Sediment tested for contaminants prior to disposal to landfill or reuse

|

Within 2 working days from

completion

|

All

contractors are required by Council to have an OH&S Policy in accordance

with the NSW OHS Act 2000 and OHS Regulation 2001 which aim to secure

and promote the health, safety and welfare of people at work. Employers and

supervisors of staff and contractors have a duty of care under the Act to

protect employees and demonstrate due diligence in their OHS Management

Systems. Council and contractor policies must address:

· certificates of currency for public liability and

professional indemnity insurance, third party

· motor vehicle insurance and workers compensation

· safe work practices and procedures (hazard

identification and risk analysis per site/device)

· induction and safety training (Green or White card)

· corrective action and documentation

· incident / accident recording and investigation

· personal protective equipment (PPE)

By ensuring

these requirements are met by both Council staff and contractors the risks

identified during the cleaning and maintenance process can be analysed,

evaluated and risk treatment plans implemented in accordance with AS/NZS 4360 Risk Management.

|

Hornsby Shire Council

|

Attachment to Report No. EN38/08 Page 11

|

The principal

objective of stormwater treatment measures is to improve the quality of

stormwater by removing pollutants, including litter, sediment, nutrients and

associated bacterial contamination. Stormwater structural treatment measures

can be grouped into three categories: primary, secondary and tertiary (Victoria

Stormwater Committee, 1999)

Table 3.0 Pollutant sizes and treatment

measure (Adapted from Engineers Australia, 2006)

|

Treatment Category

|

Treatment process

|

Typical

retained contaminants

|

Treatment measure

|

|

Primary

|

Physical screening or rapid sedimentation techniques

|

Gross pollutants and coarse sediment

|

GPT, sediment basins

|

|

Secondary

|

Finer particle sedimentation and filtration

techniques

|

Fine particles and attached pollutants

|

Sediment basins, Biofilters

|

|

Tertiary

|

Enhanced sedimentation and filtration, biological

uptake, adsorption onto sediment

|

Nutrients and heavy metals

|

Wetlands, Biofilters, Stormwater gardens

|

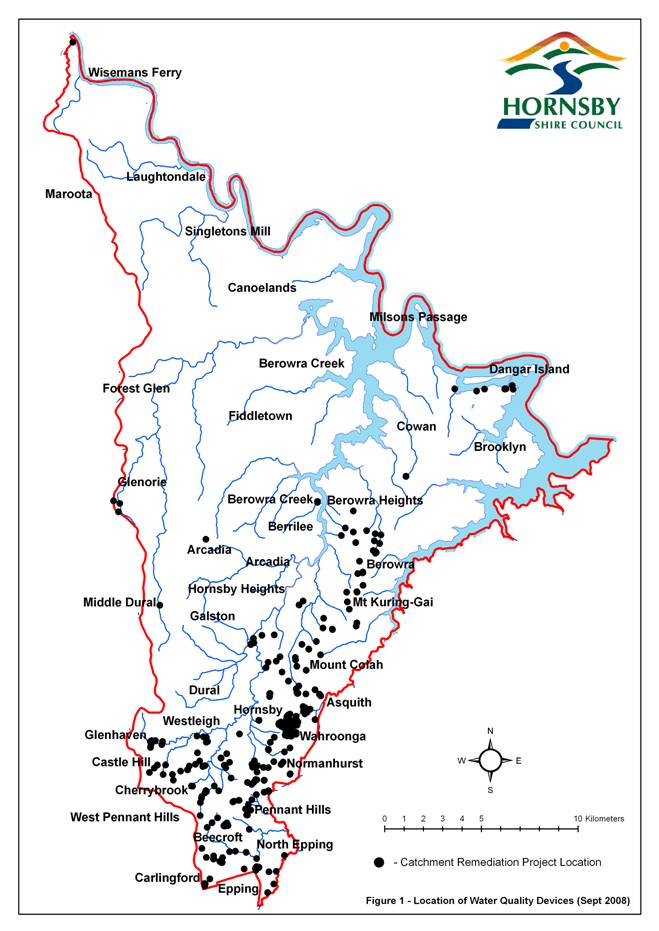

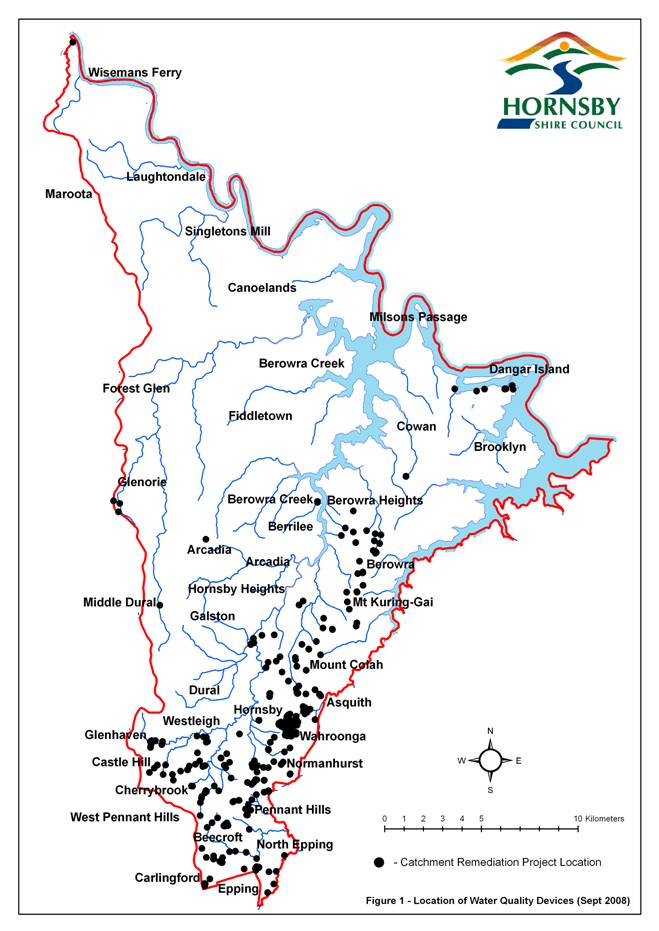

In 2007/2008,

16 catchment remediation rate capital works projects were completed at a total

cost of $957,000. These works involved the construction of 11 sediment basins,

four end-of-pipe gross pollutant traps, eight stream remediation projects, one

bioremediation basin and six stormwater gardens. These projects are detailed in combination

with previously constructed devices across Hornsby Shire (Locations mapped in

Figure 1) and are in bold for easy

differentiation.

Gross

pollutants are typically those materials greater than 0.05mm, both degradable

and non-degradable, which detrimentally impact physically, visually and

bio-chemically on aquatic ecosystems. For the purposes of this report, a gross

pollutant device (GPD) can take many forms including traditional gross

pollutant traps with trash racks (refer to photo below), litter baskets, nets,

pit inserts and underground sumps. Some

GPD’s are fabricated to fit specific locations, whereas others are bought off

the shelf (proprietary devices). At

present over 370 GPD’s have been installed and constructed throughout the Shire.

3.1.1.

Trash Rack, Water

St, Hornsby

|

|

Trash Racks (21)

|

Norwood

Avenue,

Beecroft

|

Clarinda Street,

Hornsby Clarinda Street,

Hornsby

|

|

Berkley Close, Berowra

|

Malsbury Road, Hornsby

|

|

The Gully

Road, Berowra

|

Old Berowra

Road, Hornsby

|

|

Warrina

Street, Berowra Heights

|

Hamley Road, Mt Kuring-gai

|

|

Belltree

Place, Castle

Hill

|

Denman Parade, Normanhurst

|

|

Woodgrove

Road,

Cherrybrook

|

Bellamy

Street,

Pennant Hills

|

|

Odney Close, Cherrybrook

|

The Comennara

Parkway, Thornleigh

|

|

Beecroft Road, Epping

|

Larool Cresent, Thornleigh

|

|

Tekopo Road, Glenorie

|

New Farm

Road, West Pennant Hills

|

|

Northcote

Road,

Hornsby

|

Wilga Street,

West

Pennant Hills

|

|

Water

Street, Hornsby

|

|

|

Mittabah Road, Asquith

|

Shepherds

and Macquarie Drives, Cherrybrook

|

|

Wattle

Street, Asquith

|

Clovelly Road, Hornsby

|

|

Sutherland Road, Beecroft

|

Burdett and

Sherbrook Roads, Hornsby

|

|

Bambil Road, Berowra

|

The Comenarra Parkway,

Thornleigh

|

|

Berowra Waters Road, Berowra

Heights

|

Janet Avenue, Thornleigh

|

|

Stratford Place, Asquith

|

Gleneagles Crescent, Hornsby

|

|

Baldwin Avenue, Asquith

|

Clarinda Road, Hornsby

|

|

Joalah Crescent, Berowra

|

Sherbrook

Road, Hornsby

|

|

Ti-tree

Close, Berowra

|

Binya Close, Hornsby

|

|

Childrey Place, Castle Hill

|

Raphael

Drive, Hornsby Heights

|

|

Kenburn Avenue, Cherrybrook

|

Pacific Highway, Hornsby

Park

|

|

Flametree

Close (West), Cherrybrook

|

Parklands

Road, Mount Colah

|

|

Flametree

Close (East) , Cherrybrook

|

Jessica Place, Mount

Colah

|

|

Pecan

Close, Cherrybrook

|

Pacific Highway, Mount

Kuringai

|

|

Glenoak Way, Cherrybrook

|

Pacific Highway, Mount

Kuringai

|

|

Alberta Avenue, Cowan

|

Hinemoa Avenue, Normanhurst

|

|

New Line Road, Dural

|

Brittania Street, Pennant Hills

|

|

Ridge

Street, Epping

|

Brittania Street, Pennant

Hills

|

|

Pembroke

& Stanley Road,

Epping

|

Blantyre Place, Thornleigh

|

|

Galston Road, Galston Gorge

|

Blantyre Place, Thornleigh

|

|

Burdett Street, Hornsby

|

Duneba Drive, Westleigh

|

|

Rosemead Road, Hornsby

|

Duneba Drive, Westleigh

|

Channel Nets, Burdett St, Hornsby

Nettech, Pacific Hwy,

Hornsby

|

|

|

Dudley Street, Asquith

|

Millbrook Place, Cherrybrook

|

|

Gardenia

Street, Asquith

|

Monterey Place, Cherrybrook

|

|

Jacinta Avenue, Beecroft

|

Rosemary Place, Cherrybrook

|

|

The Gully Road,

Berowra

|

End Lockyer Place,

Dural

|

|

Woodcourt Road, Berowra

Heights

|

Pike Road, Hornsby

Heights

|

|

Dusthole Bay, Berowra Waters

|

Hunter Street, Hornsby Mall

|

|

George Street, Brooklyn

|

Sefton Road (Council Depot), Thornleigh

|

|

Dangar Road, Brooklyn

|

Dartford Road (Road Reserve), Thornleigh

|

|

Foley Place, Castle Hill

|

Unwin Road, Waitara

|

|

Castle

Howard Road, Cheltenham

|

Boyd Avenue, West Pennant Hills

|

|

Anthony Street , Carlingford

|

George Street, Pennant Hills

|

|

Off Heights Place, Hornsby Heights

|

Old

Northern Road, Wisemans Ferry

|

|

Beecroft/Carlingford/Epping (35)

|

Pennant

Hills Commercial area, Pennant Hills (4)

|

|

Mills Park Tennis Carpark, Asquith

|

Thornleigh

Industrial/Commercial (11)

|

|

Wattle

Street, Asquith (3)

|

Thomas and

Orara Streets, Waitara (6)

|

|

Berowra Waters Road & Pacific

Hwy, Berowra (4)

|

Eucalyptus Drive, Westleigh Eucalyptus Drive, Westleigh

|

|

Dusthole Bay, Berowra Waters

|

|

|

Brooklyn Road, Brooklyn (5)

|

|

|

Cairnes Road, Glenorie

|

|

|

Hornsby

Industrial area, Hornsby (20)

|

|

|

Dural

Street, Hornsby (3)

|

|

|

Hornsby CBD (70)

|

|

|

Pacific Highway, Mount

Colah

|

|

|

Sue Place, Mount

Colah (2)

|

|

|

Denman Road, Normanhurst (2)

|

|

Pit

Insert, Dural St, Hornsby

|

|

Natural wetlands are transitional environments between

terrestrial and aquatic habitats. They are characteristically shallow

environments that are cyclically, intermittently or permanently inundated by

fresh, brackish or saline water. Wetlands provide habitat for biota such as

emergent macrophytes, macroinvertebrates, amphibians, reptiles and birds which

are dependant on the inundation of the wetland.

In managing urban stormwater pollution of natural

waterways, constructed wetlands are often built to mimic nature and to achieve

improvements in stormwater quality through natural physical and chemical

processes. Furthermore, they provide additional benefits through the provision

of habitat for aquatic and terrestrial fauna, maximising biodiversity and

enhancing aesthetics.

To date, Council has constructed wetlands funded

through the Catchments Remediation Rate (CRR) at the following locations:

|

Lamorna

Avenue,

Beecroft

|

Clarinda

Street,

Hornsby

|

|

Midson Road, Beecroft

|

Clovelly Road, Hornsby

|

|

Plympton Road, Beecroft

|

Laurence

Street,

Pennant Hills

|

|

Brooklyn Road, Brooklyn

|

Dartford Road, Thornleigh

|

|

Hastings Park, Castle Hill

|

John Savage

Crescent, West Pennant Hills

|

|

Ridge Street, Epping

|

Boundary Road, West Pennant Hills (Wallameda)

|

|

Sallaway Road, Galston

|

|

Midson Rd Wetland, Beecroft

|

|

Hornsby Shire Council maintains

fifty-nine (59) sediment basins throughout the Shire which have either been

constructed under the Catchments Remediation Program.

Council

scheduled the cleaning of a number of established basins in 2007/2008. It is

important that sediment basins are cleaned at least bi-annually (or at 30%

capacity) so as to prevent colonisation of weeds and the release of potentially

bio-available contaminants caused by disturbance events (eg. scour and

re-suspension).

During 2007/2008, 11 new basins*

were constructed at:

|

Boundary Street, Berowra

|

Stewart

Avenue , Hornsby

|

|

Castle

Howard Road, Cheltenham

(x2)

|

Murralong

Road, Mount

Colah

|

|

Kirkham

Street, Cheltenham

(x2)

|

Nicholas

Crescent, Normanhurst

|

|

Alberta

Avenue, Cowan

|

Duneba

Drive Westleigh

|

|

James Henty

Park, Dural

|

|

*The ten new basins

were included in the 59 sediment basins that council currently maintains.

Newly constructed

sediment basin, Kirkham Street,

Cheltenham

|

|

Many creeks become physically degraded when the natural

hydrology of the catchment is altered. This most often results in creek bank

scour and erosion which is accelerated through processes such as the clearing

of riparian vegetation and increased stormwater runoff from impervious

surfaces. This degradation can have a detrimental impact on water quality often

resulting in an increase in sediment transport and associated sediment bound

contaminates.

Aquatic flora and fauna are impacted through a loss of

habitat, increased competition with weeds, poor light penetration into the

water column due to increased turbidity levels and smothering of benthic

organisms with increased sedimentation.

In the remediation of a degraded section of stream the

following techniques are used:

· Creek bank stabilisation -

Typically using locally sourced

sandstone boulders that prevent the creek bank from eroding any further, and

provide habitat for fauna and flora on the rock surface and in cracks between

rocks. A variety of softer creek bank armouring strategies are also incorporated,

including the pinning or staking of jute mesh/matting, woven blankets, fallen

logs and chain-wire mesh. These approaches are often combined with native plant

cells or tubestock.

· Meanders - To aid in the reduction of flow velocities during

storms.

· Riffle zones and natural

rock fall structures - Are used to

provide in-stream habitat, stabilise the creek bed, aerate the water and allow

maximum UV light treatment from sunlight to destroy faecal bacteria.

· Pool zones - Are incorporated to create habitat for fauna and

macrophytes and to dissipate flow velocities which allows sediments to drop out

for later removal.

· Revegetation of riparian

zone - This zone is planted with

indigenous native tubestock to improve habitat, enhance faunal corridors and

vegetation links, provide a food source for both terrestrial and aquatic

organisms and to stabilise the banks.

· Stabilising stormwater outlets - Rock armouring around stormwater outlets reduces

erosion and scour caused by high flows.

Sites that have undergone stream remediation since

implementation of the Catchments Remediation Program have been summarised in

Table 3.1. In 2007/2008, eight (8) new sites

underwent creek remediation works in the suburbs of Cheltenham, Berowra,

Normanhurst, Westleigh, Hornsby and Mount

Colah and are highlighted

in bold.

|

|

Creek

remediation works, Duneba

Drive, Westleigh

|

|

Table 3.1 Stream

Remediation Projects in the Hornsby Shire

|

Berowra Creek

Catchment

|

Lane Cove River Catchment

|

|

|

|

|

Berowra – Boundary

Street

|

Beecroft – Fearnley Park

|

|

Castle Hill –

Hastings Park

|

Beecroft – Lamorna Avenue

|

|

Cherrybrook –

Woodgrove Road

|

Beecroft – Midson Road

|

|

Hornsby – Clarinda Street

|

Beecroft – Norwood Avenue

|

|

Hornsby –

Reddy Park

|

Beecroft – Plympton Road

|

|

Hornsby – Stewart

Avenue

|

Beecroft –

Ray Park

|

|

Hornsby Heights – Heights Place

|

Carlingford – Anthony

Street

|

|

Mount Colah – Murralong

Road

|

Cheltenham – Castle Howard Road

|

|

Mount Colah –

Parklands Road

|

Cheltenham – Kirkham Street

|

|

Pennant Hills

– Laurence Street

|

Epping – Kent Street

|

|

West Pennant

Hills – John Savage Crescent

|

Epping – Ridge Street

(west)

|

|

West Pennant Hills – Wilga Street

|

Normanhurst –

Hinemoa Avenue

|

|

Westleigh – Duneba

Drive

|

Normanhurst – Nicholas

Crescent

|

|

Westleigh – Eloura

Road

|

Pennant Hills

– Orchard Street

|

|

|

Thornleigh –

The Comenarra Parkway

|

|

Cowan Catchment

|

Epping – Ridge Street (east)

|

|

Hornsby Ck – Sherbrook

Road

|

Epping – Pembroke Road

|

|

|

Epping – Stanley Street

|

|

Hawkesbury River Catchment

|

Cherrybrook – Flametree Crescent

|

|

Brooklyn – Brooklyn Road

|

|

In addition, the majority of gross pollutant devices

discussed in this report also incorporate some stream remediation to stabilise

banks around the devices and improve habitat immediately up and downstream.

Although the environmental benefit of stream

remediation works is difficult to quantify, the works provide a significant

benefit in terms of a reduction in erosion and associated sediment loads moving

to the lower reaches of the creeklines and receiving waters, improved native

riparian and aquatic habitat and enhanced visual aesthetics.

3.6 Bioremediation Basin

- Castle Howard Road,

Cheltenham

In March 2008, Council began work on a bioremediation

system in Cheltenham to treat urban stormwater

to a tertiary level. The system encapsulates the “treatment train” approach by

combining the use of a GPD, porous piping and bioremediation basin.

Gross pollutant device: To ensure optimal performance and prevent clogging

of the system a CDSâ Unit has

been installed. This unit uses vortex forces to remove larger refuse and

sediment, which is stored in an offline sump, before delivering stormwater to

the bioretention basin.

Gross pollutant device: To ensure optimal performance and prevent clogging

of the system a CDSâ Unit has

been installed. This unit uses vortex forces to remove larger refuse and

sediment, which is stored in an offline sump, before delivering stormwater to

the bioretention basin.

Porous piping:

After leaving the CDS unit, stormwater (free of gross pollutants) is directed

into specially designed porous concrete pipes. Stormwater exfiltrates (leaks)

through the permeable walls of the pipe into the surrounding substrate filter

media. During this process mechanical filtration takes place. Furthermore,

biofilms develop within the porous pipes system which assists by digesting

pollutants, such as organics and nutrients.

Porous piping:

After leaving the CDS unit, stormwater (free of gross pollutants) is directed

into specially designed porous concrete pipes. Stormwater exfiltrates (leaks)

through the permeable walls of the pipe into the surrounding substrate filter

media. During this process mechanical filtration takes place. Furthermore,

biofilms develop within the porous pipes system which assists by digesting

pollutants, such as organics and nutrients.

Bioremediation

basin: When the exfiltration capacity

of the pipes is reached (that is, water is coming in faster than it leaks out)

then the stormwater will surcharge (back–up) into the basin itself and

percolate vertically down through the vegetation and filter media.

Both the vegetation type and filter media (loamy sand)

have been specified to comply with the latest findings from current research to

maximise the treatment performance of the bioremediation basin. While the concept is simple thousand of hours

of research, both nationally and internationally, have gone into determining

the most favourable specifications.

Both the vegetation type and filter media (loamy sand)

have been specified to comply with the latest findings from current research to

maximise the treatment performance of the bioremediation basin. While the concept is simple thousand of hours

of research, both nationally and internationally, have gone into determining

the most favourable specifications.

High flow

by-pass: The system also has a high

flow diversion channel installed to redirect high stormwater flows that may

damage or erode the filter media and vegetation from the system.

As this is the first system of this specific design configuration

to be constructed in Hornsby Shire Council it is planned to undertake sampling

up and downstream of the basin to determine its effectiveness at reducing

pollutant concentrations. This will be done using automated samplers that

provide the ability to sample stormwater from rain events before and after

stormwater has passed through. Results from this sampling program will be used

to determine whether similar systems will be installed elsewhere throughout the

Shire. They will also add to a growing

database of work being done nationally on the development of best practise

stormwater quality management. Furthermore, the site will be used as a demonstration

site to educate other local governments and the general community in the

benefits of bioremediation in treating stormwater.

3.7 Stormwater Gardens - Turner

Road, Berowra

In June 2008, Council completed the installation of

six stormwater gardens on Turner Road,

Berowra. These systems (also known as

biofilters or bioremediation systems) have been demonstrated to be effective at-source

structural stormwater pollution control measures (Fletcher et al 2005).

Stormwater flows over the vegetated area and slowly

percolates through the filter media. Pollutant removal is achieved though the

interface of the vegetation and filter media as a result of enhanced

sedimentation in the vegetation zone, mechanical filtration, sorption and other

chemical processes in the filter media and plant and biofilm uptake of

pollutants (Hatt et al 2006). An underdrain collects the treated water and

delivers it to existing stormwater infrastructure.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of the

six stormwater gardens installed on Turner Road, Berowra (Illustration reproduced courtesy of Brisbane City Council)

|

|

Hornsby Shire Council currently requires developments

greater than 2500 square metres in area to provide permanent stormwater quality

treatment devices on or adjoining their subject sites. Developers are

conditioned by Council to also provide maintenance during the construction

phase in accordance with an approved Asset Maintenance Plan. Following

completion of the development, two scenarios can result:

1. Developer

Constructed, Council Maintained

These devices were installed by Developers as a

condition of development consent (usually Torrens Title) and have been taken

over by Council to maintain after which 80% of the lots have had dwellings

erected and occupied. Council will usually seek a financial contribution from

the developer towards operating and life cycle costs.

2. Developer

Constructed, Community Association Maintained

These devices have also been installed by Developers

as a condition of development consent and either, continue to be maintained by

developers in the short term or are the responsibility of the body corporate to

maintain under Community or Strata Title.

Council currently keeps a record of these stormwater

quality assets in order to ensure all maintenance complies with the consent

conditions post-occupation. Council usually reaches a mutual agreement with developers

to take over the basins as Council assets, in return for a sum of money which

has been estimated to sustain the maintenance of basins over a 20 year life

cycle.

Listed below are sites where developer built wetlands

and sedimentation basins required have been constructed as a condition of

development consent. It should be noted that only the Shepherds Drive,

Cherrybrook and Sydney Road,

Hornsby Heights constructed wetlands are

currently under the care, control and management of Council. The remaining

wetlands are managed by Community Associations or developers under approved

Plans of Maintenance.

|

Summer Hill

Way,

Berowra

|

The Outlook, Hornsby Heights

|

|

Foley Place, Castle Hill

|

Kalang Road, Mount

Colah

|

|

Shepherds Drive, Cherrybrook (The Lakes)

|

Huntingdale

Way,

Thornleigh

|

|

Millstream Grove, Dural

|

Wild Ash

Avenue, Thornleigh

|

|

Sydney Road, Hornsby

Heights

|

The Sanctuary, Westleigh

|

|

Hornsby Shire Council

|

Attachment to Report No. EN38/08 Page 22

|

Daily

rainfall data is obtained from the Bureau of Meteorology at nine sites across

the Shire. This data is used to examine the relationships between total yields

of gross pollutants and rainfall. In 2007/2008 the Hornsby Council area

recorded above average annual rainfall and was subject to a high proportion of

large rainfall events (Refer to Appendix A for statistical data). This explains

the comparative increase in yields referred to in following section.

The collection of performance data

over the 2007/2008 financial year has allowed Council to examine the indicative

maintenance costs and gross pollutant removal trends for the 370+ water quality

improvement devices in the LGA. The results indicate that in 2007/2008 the

gross pollutant devices have served to remove approximately 1236 cubic metres

of sediment, litter and organic matter from the Shire’s waterways. These volumes were large and can be best

explained by two anomalies:

1. The

above average rainfall that resulted in greater volumes of pollutants being

mobilised and captured (refer to figure 4.3); and

2. The

higher than normal sediment and organic yield resulting from the cleaning out

of a number of sediment basins and the dredging of the Lakes of Cherrybrook

(150m3). As a result, sediment volumes accounted for approximately

48% of the total pollutant load captured, litter 5% and organic matter 47%.

The following

series of figures examine the performance of GPD’s in 2007/2008 and against

previous years.

Figure 4.1: The relationship between average monthly volume of gross pollutants

and average monthly rainfall.

When pollutant volume is analysed against average

annual rainfall all three categories of gross pollutants are mobilised and

captured after only 10 mm of rainfall, evident on the graph by the steep rise

in the curve. This phenomenon is referred to as the “first flush” effect, after

which the volume captured continues to rise at a much slower rate in relation

to rainfall volumes.

It can be seen that the load of litter recovered from

all devices over the period is fairly consistent for all size rainfall events

(indicated by the flat dotted line). This is most likely due to the fact that

litter is readily mobile and floatable in the formal drainage system (curb,

gutter and pipes) and most of it will be flushed and collected in downstream

GPD’s, even in small rain events. However, the fact that the curve for sediment

is steadily climbing, proportional to rainfall, illustrates that after the

initial flush the transport of sediment is directly proportional to stormwater

volumes and associated energy.

Figure 4.2:

Volumes of pollutants removed from GPD’s (2007-2008)

The actual volume of pollutants removed from month to

month varied greatly in the 2007-2008 period. A clear correlation between

monthly removal rates and rainfall cannot be made due to: 1) variable lag times

between rainfall events and cleaning events, and 2) the disproportionally high

volumes removed from sediment basins and wetlands which are in addition to

regular cleaning events.

However,

a strong correlation is found between rainfall and pollutant yield from Council’s

GPD’s when viewed annually, as shown in Figure 4.3. With increased rainfall there is increased

stormwater run-off into Council’s drainage system that results in pollutants

being mobilised, transported and trapped by GPD’s.

Figure 4.3:

Pollutant volume removed from GPD's against average annual rainfall over the

last three years

Figure 4.4 Prediction of annual gross pollutant rates using

landuse area.

Hornsby Shire Council is now at a stage

where the data gathered from the various gross pollutant devices can be used to

predict the annual gross pollutant (export) rates on the basis of landuse.

Figure 4.4 shows how the annual export rate of pollutants exponentially

increases with the amount of catchment that is urbanised (excludes

bushland/open space). This information can be used when planning for future

devices, in terms of expected export rates and known device capabilities.

Stormwater managers can then compare actual pollutant export rates with the

predicted values in order to gauge the efficiencies of devices through time.

The high frequency of Hornsby Council’s inspection and

cleaning of the devices combined with the unique trap designs for ease of

maintenance, ensures that the pollutant trapping efficiency is optimum for each

storm event and that materials do not decompose or stagnate causing additional

problems with the release of pollutants into the water column.

The

total cost to Council to maintain its water quality assets and adjacent

landscaped areas was approximately $347,000 in the 2007/2008 financial year ($257,000

for cleaning/maintenance, $90,000 for landscaping/vegetation maintenance). This

cost included device inspections, cleaning and desilting, material processing

for reuse, disposal of litter to landfill, asset maintenance and repair,

landscape maintenance and weed control in and around assets and maintenance of

leachate treatment and reuse facilities. However, the higher than expected

costs were as a result of two one-off maintenance projects:

· Remediation

of Mt Colah stockpiling site: $87,000 (Refer to section 4.4 for further

detail);

· Dredging

of Lakes of Cherrybrook: $45,000

Table 4.0 presents the averages in terms

of capital investment and operational cost for individual basket, trash rack

and proprietary devices from the period June 2001-June 2008. The average annual

installation and maintenance cost per hectare of catchment for proprietary

traps is still quite high in comparison to the traditional trash racks and

baskets. However, the proprietary devices average annual capture per hectare

offsets these higher costs by being superior to the traditional devices, mainly

as a result of their closer proximity to the pollutant source.

Table 4.0

GPD Comparative Costs from July 2001 - June 2008

|

Device

|

Average Clean Cost $

|

Average Annual Maintenance Costs $/yr *

|

|

Trash Rack (n=21)

|

200

|

1,466

|

|

Large Trash Basket (n=10)

|

92

|

631

|

|

Proprietary Device (n=58)

|

143

|

2079

|

|

Pit inserts

(n=170)

|

17

|

203

|

In March

2008, as part of the CRR maintenance program, Council initiated dredging works

at the Lakes of Cherrybrook. This activity involved the removal of depositional

material (organic matter and sediment) from the upper and lower ponds.

Contractors dredged the lower pond using a walking excavator and trucks. Sediment plumes on both the tributaries to

the upper pond were removed in a less invasive manner through the use of

eduction trucks.

The

dredging works form part of an overall water quality and ecological improvement

initiative for the lakes embarked upon under the CRR program in 2008. Other

components of the initiative proposed in 2008/2009 include:

· Installation

of aerators in both ponds to increase dissolved oxygen levels, enhance water

quality and hopefully reduce the prevalence and severity of Botulism outbreaks.

· Deployment

of rafted reedbeds in the lower pond, which act as floating wetlands and

provide high levels of water quality treatment.

·  Planting of native aquatic

plants at the interface between water and land to enhance water treatment,

stabilise banks and provide habitat.

Planting of native aquatic

plants at the interface between water and land to enhance water treatment,

stabilise banks and provide habitat.

Contractors

removing dredge spoil, Lakes of Cherrybrook Lower pond after

dredging, Lakes of Cherrybrook

|

|

A summary of wetland related annual costs and

monitoring data is contained in Table 4.2. The average maintenance cost for

Council’s major wetlands is calculated at $3,035 per site per year (or 1.6% of

the average capital cost).

The size of catchments draining to these constructed

wetlands ranges from 15-400 hectares. The average pond surface area to

catchment area ratio calculates at 0.23% which is below the minimum design size

recommended by DLWC (1998) of 2% of the catchment area. It should be noted that

this recommendation does not account for the variability associated with

different catchment land uses, pollutant loads, peak flows, topography and

soils. It is best used to determine preliminary wetland feasibility. Because

the nature of Hornsby Shire is so topographically constrained (ridge top

development that does not afford large areas for wetland construction) and

contains significant remnant bushland, the wetland feasibility threshold is

much lower than average.

Water

quality monitoring of five separate systems managed by council over the past 10

years has shown that levels of total nitrogen, phosphorus, suspended solids and

faecal coliforms are significantly reduced under base flow and small storm flow

events. Monitoring results are based on both grab and load-based samples (and

multi-probe analytes) obtained by Council over multiple rainfall events and

inter-events.

Two

wetland sites were monitored during 2007-2008 period (Refer to the Water

Quality Annual Report 2007/2008 fro statistical analysis). Sampling was not

undertaken during large stormflow events. Clarinda Wetland was removing on

average approximately 40% of Total Nitrogen and Oxidised Nitrogen, 50% Ammonium

Nitrogen, 60% Faecal Bacteria and 30% Suspended Solids. Cherrybrook Lakes

was found to be removing approximately 60% Total Nitrogen, Ammonium Nitrogen

and Oxidised Nitrogen, 40% Phosphorus and 70% Faecal Coliforms. However, there

was an average increase of Suspended Solids from 5 to 6.8 mg/L., probably

resulting from an increase of algae and organic debris in the open water bodies

and a nett decrease in dissolved oxygen in water flowing out of both wetlands,

indicating oxygen was taken up by microbial and vegetative materials in the

deeper still waters.

Table 4.2 Constructed

Wetland annual costs and monitoring records to date.

|

Wetland

|

Capital Cost $ (Year)

|

Pond Surface Area

(m2)

|

Pond Surface Area to Catchment Area (%)

|

Cost per m2 of pond

($/m2)*

|

Average Annual Maint. Cost2

($/yr)

|

Monitoring Data

(year/s)

|

|

Laurence St, Pennant Hills

|

135,000 (1996)

|

225

|

0.06

|

619

|

4,227

|

June 1995 – June 2002

|

|

Boundary

Rd, West Pennant Hills

|

288,000 (1996)

|

1875

|

0.14

|

158

|

7,7613

|

August 1998 –

June 2002

|

|

Plympton Rd, Beecroft

|

305,000 (2000)

|

350

|

0.06

|

875

|

1,187

|

November 99 – June 2002

|

|

Brooklyn Rd, Brooklyn

|

46,000 (1997)

|

205

|

0.26

|

231

|

1,3043

|

Nil

|

|

Clovelly Rd, Hornsby

|

117,000 (1999)

|

210

|

0.02

|

561

|

819

|

Nil

|

|

Sallaway Rd, Galston

|

36,000 (2000)

|

190

|

0.01

|

193

|

664

|

Nil

|

|

Clarinda St, Hornsby

|

241,000 (2001)

|

1550

|

0.82

|

160

|

6,2273

|

July 2002 – current

|

|

Hastings Park, Castle Hill

|

445,000 (2002)

|

1500

|

0.60

|

300

|

5,054

|

July 2001 –

August 2003

grab & load

|

|

Midson

Rd, Beecroft

|

252,000 (2003)

|

1220

|

0.03

|

208

|

2,1213

|

Nil

|

|

John Savage Cres, West Pennant Hills

|

203,000 (2004)

|

1050

|

0.09

|

194

|

1,0733

|

Nil

|

|

Lamorna Ave, Beecroft

|

134,0004

(2005)

|

400

|

0.44

|

347

|

4,946

|

Nil

|

|

Dartford Rd, Thornleigh

|

80,000

(2006)

|

250

|

2.27

|

324

|

1036

|

Nil

|

|

Mean

|

190,000

|

752

|

0.4

|

348

|

3035

|

NA

|

|

1 Includes monthly grab sampling (wet/dry) and probe (total of 13

parameters). Analysis by NATA lab

2 Includes weeding/spraying, sediment/rubbish/debris removal,

planting/mulching and replacement and reporting (excludes volunteer Bushcare

labour)

3 Volunteer Bushcare present onsite

4 Capital costs incorporates up to 100m of stream remediation

*Cost/m2 of

pond is calculated using capital cost and average annual cost/year

|

The CRR

maintenance program aims to reduce the quantity and cost of disposing of

recovered material to landfill by reuse and recycling within the LGA. This

activity has been undertaken by Council for a number of years and is seen as

being ecologically and financially sustainable.

However,

due to the increasing volumes that were being removed from GPD’s in 2007/2008,

due to above rainfalls the amount of material that needed to be stored and

mechanically sorted was becoming too large to be accommodated at the designated

site in Mt Colah. Therefore, the decision was made in early 2008 to cease this

activity until a more suitable site could be sourced and established. The Mt

Colah site was cleared of all residual material and remediated at a cost of

$87,000.

Until a

future site is found, Council will incur ongoing disposal costs for GPD

material in excess of $120,000 per annum based on extraction and disposal

volumes from the previous two years. This cost is up to 80% more than is

required when we are able to sort and reuse the material within the LGA.

Furthermore, the material is now being exported to landfill sites outside of

the Shire. This position is neither ecologically or financially sustainable,

therefore Council staff will be pursuing all avenues to source a suitable site

for material sorting and stockpiling.

5.0 LANDSCAPE MAINTENANCE

AND BUSH REGENERATION

Due to the increasing number of devices being built

and the resulting demand for timely and efficient maintenance, Council has

continued to engage bush regeneration contractors on a 3 year basis. The

contracts are annually renewed based on a performance evaluation of the

previous year’s work and compliance with the conditions of the contract.

The key objectives of the contract are:

i) to maintain planted native vegetation around water

quality structures and nominated wetlands, using methods that have minimal

environmental impact on aquatic organisms and water quality;

ii) treatment and eradication of any riparian and

aquatic weeds giving priority to the treatment of categorised noxious weeds,

applying herbicide according to manufacturers specifications and in a

responsible and recorded manner (in terms of both environmental and personal

safety); and

iii) to provide a maintenance report for each site

after treatment, including a more detailed maintenance report for the wetland

sites which is required to assess the extent of plant growth and site recovery

from weed infestation.

In 2007/2008, contractors were responsible

for landscape maintenance around eighty plus sites at a cost of $57,690 (1825

hours). This involved weeding and spot spraying of the immediate area

surrounding each water quality control asset including landscaped areas that

have been mulched and planted with local native species. Some replacement

planting and staking of existing tubestock is also required. Newly constructed

devices will also require planting of terrestrial tubestock and in some cases,

aquatic (macrophyte) plantings, with all plant stock being supplied by Council’s

nursery. Maintenance reports and invoices are submitted to Council on a

fortnightly basis. Targeted terrestrial weed species include - Privet, Camphor

Laurel, Lantana, Blackberry, Turkey Rhubarb, Castor Oil plant, Balloon Vine,

Madeira Vine, Honeysuckle, Morning Glory, Asparagus Fern, Mist Flower, Crofton

Weed, Ochna, Ginger, Wandering Jew and other herbaceous weeds and grasses such

as Kikuyu and Paspalum.

This involves the maintenance weeding/spraying of

riparian areas and removal of weeds and nuisance plants within the shallow

wetland ponds. In 2007/2008, contractors were

responsible for maintaining 14 wetland sites at a cost of $33,000 (this

includes four wetlands not built using funding from the CRR budget). Of this

$33,000, 80% was dedicated to Councils four largest wetlands (Wallumeda, Laurence Street, Hastings

Road and Clarinda Street).

Time is also allocated to the removal of stormwater litter/rubbish strewn

throughout the pond and edge areas. Replacement planting with macrophytes is

also carried out, including occasional wetland establishment at new sites. A

wetland maintenance sheet is required to be completed when conducting works

within wetlands, as Council requires this information for wetland condition

monitoring.

Target aquatic weed species include Typha

(Bullrush), Barnyard Grass, Milfoil, Watercress, Cyperus eragrostis and other undesirable or noxious water plants

(e.g. Ludwidgia (peruviana), Alligator Weed and Salvinia). If a W1 Noxious Weed

category plant is found onsite, the Contractor is to immediately notify Council

as required under the Noxious Weeds Act

1993.

|

|

John Savage Wetland,

West Pennant Hills: Contractors planting aquatic plants

|

|

|

Hornsby Shire Council

|

Attachment to Report No. EN38/08 Page 31

|

The Catchments Remediation Program has also been

responsible for funding the treatment of polluted leachate from two of the

Shire’s largest former municipal tip sites at Arcadia

Park, Arcadia and Foxglove Oval, Mt Colah. Instead of using the traditional technologies

available for the treatment of leachate, Council has looked to more sustainable

and innovative methods that can achieve pollution reductions and serve as a

model for leachate treatment at a local government, state and national level.

This work is significant by

way of the methodology which mimics natural processes of nitrification and

denitrification. Council staff have worked together in a trans-disciplinary

manner, together with specialised scientific consultants to design, construct

and monitor both treatment systems. Council is committed to the long-term

maintenance, monitoring and management of the two facilities in order to

justify and apply the technological benefits to other landfills within the

Shire. Monitoring to date has revealed a dramatic reduction in ammonia which

has maximised the opportunities for reuse on adjoining open space and

landscapes.

Foxglove waste disposal site was in operation from

1963 to 1980. This site produces approximately 10,000L/d of leachate due to the

location of the tip on an existing drainage line, and the lack of a sound

impervious capping layer over the oval. The main environmental concern within

the leachate is the elevated ammonia concentrations ranging between 40 and 200

mg/L.

Stage 1 of the rehabilitation process has been

completed, which involved capturing the leachate using a leachate cut off

drain, collection well, pump and soakage pit at the base of the landfill. The collected leachate is then pumped to a two-cell (vertical and

horizontal flow), soil-based reed bed (shallow wetland) which significantly

improves the quality of leachate leaving the fill. This treated leachate is

then pumped to and irrigated (below ground drip) over the adjoining native

woodlots and park. Costing around $300,000 to install, the system is able to

treat around 10,000 L/day of ammonia rich leachate and has minimal ongoing

costs. It has been calculated that the system saves Council about $40,000 p.a.

(in lieu of waste water disposal costs).

The final stage of the leachate remediation was

completed in Febuary 2008 and has involved the installation of a bio-reactor to

treat 4,500-6,000L of leachate a day to a level compatible with standards for

irrigation reuse. Developed and patented by Biospot P/L, the bio-reactor technology uses a process whereby Nitrosomonas and Nitrobacter

are immobilised on a carrier (that is, bacteria able to process nitrogen

compounds are placed in a tank “reactor” where they attach to plastic beads).

The reactor design offers “Simultaneous Nitrification (that is conversion of

ammonia to nitrite and nitrate) and Denitrification” (that is conversion of

nitrate and nitrite to nitrogen). The design of the reactor optimises the

production of nitrate and removal of ammonia from over 50mg/L to below 2mg/L. The treated water from the reactor then passes